Katherine Mould, senior talent acquisition specialist at Keywords Studios, says she was diagnosed with ADHD at age six.

She was outgoing, made eye contact, and coped well in school, but “my speech wasn’t great and I couldn’t keep up with the educational milestones of my peers,” she recalls. Her mother recognised it might be ADHD. “Her name is Diane, and Diane fought like a hellcat to get me diagnosed.”

“Because of her, I actually was able to grow up knowing that I wasn’t weird, and I was normal, and my brain was awesome.”

But Mould recognises that not everyone is so lucky – and she is adamant that we have to recognise, accept, and accommodate neurodiversity, even when it’s not ‘official’.

“One of the things that I will always scream from the rooftops is you do not need a diagnosis to be neurodivergent,” she says. “It’s not something you need a doctor to tell you you have. It’s just the way your brain works.”

“The diagnosis is not what matters, right? You wouldn’t walk up to somebody and tell them they weren’t who they were because they didn’t have a piece of paper saying that.”

Mould notes that around 15–20% of the general population is neurodivergent, but she thinks that figure is much higher within the gaming industry – possibly as high as 40–50%.

“It’s very prevalent,” she says. “But I think that’s because video games are such an awesome space for neurodivergence, right? A lot of us work remote. We’ve loved video games our whole life [because] they allow us to hyper-focus in safety. I think it’s just one of those industries that people feel safer in, so that’s where they end up.”

In a talk at Develop:Brighton entitled ‘Superpowers in Diversity: Managing Mental Health and Neurodiverse Teams for Success’, Mould outlined ways in which employers and peers could help to accommodate and encourage neurodiverse teams. The following is based on insights from the talk as well as a follow-up interview with Mould.

Acknowledging neurodiversity

Keywords has a long history of recognising and accommodating neurodiversity. Back in the early 2000s, a handful of individuals at the company set up something called the Neurodiversity Network. “This has gone from five people within Keywords to thousands,” says Mould.

The network allows employees from across the globe to share and talk about problems: Mould highlights a recent thread on the ways people struggle to work that saw senior level leaders sharing their issues. “That was so powerful,” she says. “The responses were amazing, because you’re seeing this common thread of human experience happening throughout the company.”

Mould highlights that the term neurodiversity covers a wide range of conditions. People often think of ADHD and autism spectrum disorder, but Mould highlights that it can also include people with dyslexia, dyspraxia, Tourette syndrome, and various other conditions. “There is some argument to be made that people who have depression or anxiety might also be neurodiverse, because their synapses fire differently,” she says.

“They cannot physically do what their neurotypical teammates do in those environments”

Katherine Mould, Keywords Studios

“All neurodiversity is a different way of thinking. It’s different brains that have different processing mechanisms, and [the term] recognises that neurological differences are normal and valuable within the human experience. It doesn’t mean that somebody has a problem or that they can’t process information. It just means that they might do it faster, better, or differently.”

But she notes that neurodivergent people tend to hop between jobs, only lasting a year or 18 months before they “either get burnt out or they get so overwhelmed that they start making mistakes”.

“They cannot physically do what their neurotypical teammates do in those environments, and they’ll either leave or they’ll get fired.”

This is why she is such an advocate for accommodating neurodiversity in the workplace – because by failing to do so, employers are missing out on neurodivergent ‘superpowers’.

She gives examples of how people with ADHD are often able to make decisions rapidly and quickly come up with ideas, while people on the autism spectrum can often be systematic thinkers, and people with dyspraxia can display a talent for non-linear thinking and problem solving. “These are all generalisations,” she notes. “Everybody’s gonna be different.”

One size does not fit all

But expecting neurodiverse people to thrive in an environment designed for neurotypical people is destined to fail, she thinks. “It’s like handing someone the wrong game controller and then judging them for not being able to play the game.”

“We design hiring loops and workflows and team cultures around assumptions that people are extroverted, fast paced, and noise tolerant, comfortable in social situations, and comfortable with ambiguity,” she says. Then, when a neurodiverse person struggles, “we tend to frame it as a flaw in the individual.”

Mould highlights job interview processes as one area that is often poorly designed for neurodiverse people. “Did you provide […] questions ahead of time for them?” she asks. “Or are you trying to do a ‘gotcha’ moment, which I know is very common in hiring practices? People want to see how quickly you can think – and for some of us, that can be really difficult.”

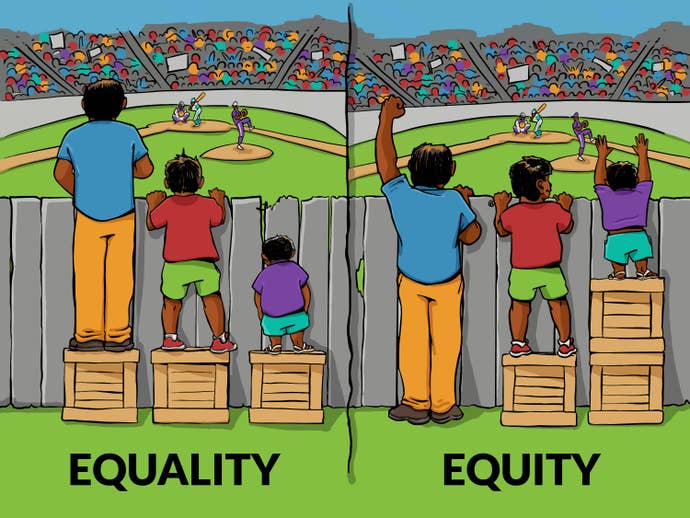

She notes that standardised interviews are often prioritised over real skill evaluation. “I know that everybody likes to ask the same question to the same people to keep things fair. And I think that people have gotten really into the idea of fairness, where that is equality over equity.”

“Equality means that everybody gets the same thing. Equity means that everybody gets what they need to succeed, essentially. So I would like to see equitable hiring practices where the questions are based on what we need for the job and the skills.”

She references the famous illustration of equality versus equity that shows three people of different heights attempting to see over a fence to watch a baseball game. “That’s the visual representation that sticks for me: for equity, it’s giving people what they need.”

“Each case is individual, each person needs a different thing to be successful,” she says. “In the workplace, one size does not fit all.”

Challenging environments

Mould explains that open-plan offices can be particularly difficult for neurodiverse people.

“Earlier in my career, everything was open plan, and everything was desk pods, and everything was ping pong tables, and free beer for lunch, and pizza parties. And that was a sensory nightmare for me, not having an office that I could close the door behind, or not having somewhere that I could just go and decompress when I got overstimulated by the lights – because LED lights and overhead lights are the devil in my world.”

She emphasises the importance for employers to provide quiet spaces. But if that’s not possible, then “even just giving the employee perk of noise-cancelling headphones can make all the difference”.

Mould also emphasises that meetings can be tricky. Her personality means that she’s often the most talkative one, but she points out that loud people “don’t always have the best ideas – sometimes it’s our quiet friends in the corner who are overwhelmed by the social situation, or they’re having a hard time processing.”

She notes that asynchronous communication – like messaging over Slack or email – is often preferable to face to face communication for neurodiverse people.

“Asynchronous communication can allow people time to process their answers to questions, and allow them to seek answers, and allow them to not feel like they have to respond immediately.”

“Asynchronous [communication makes it] easier for me to process what you’ve asked me. Because sometimes when people are talking to me, I need them to talk two or three times before my brain actually goes, ‘Oh, that’s what they said’.”

She also advises that employees must be continually assured that they don’t have to respond to messages immediately – because that can lead to panic, which in turn can lead to mistakes from not having fully processed the message.

Clear expectations

“In games, everything is shifting, everything is uncertain, and that’s just the way life is,” says Mould. “But wouldn’t it be lovely if it wasn’t, at least on your teams?”

She emphasises that providing clear expectations for exactly what each employee needs to achieve is key for accommodating neurodiversity. Vague or unclear goals are unhelpful: expectations need to be spelled out precisely.

“Don’t say, ‘Hey, I want a report on Friday’,” she explains. “That doesn’t help me. What does that look like? Do you want that input form? Do you want an entire task list? What do you want? Just be as explicit as you can – but not micromanaging.”

The same rule applies to feedback and employee evaluations. “Indirect feedback that relies on reading between the lines, this is my most hated thing,” says Mould.

She highlights Goblin Tools as a great way of breaking down tasks into manageable steps. She’s also a fan of Trello. “I love the Trello board. There is something very cathartic about moving cards across and seeing your progress.”

Similarly, she uses an AI tool to take notes at meetings. “I named him Gary,” she says, “and Gary follows me around. And Gary will not only video record the entire conversation for me, but he will also allow me to ask him questions like, ‘Hey, what did I miss?'”

“That has been game changing,’ she says, noting that her entire team has now adopted the tool, which is called Metaview. “All it does is allow me to have genuine human interaction with that person without trying to take notes,” she says. “And then at the end of it, I can go, ‘Okay Gary, I know we talked about this, can you summarise that section for me?’ And he can pull specific things for me or give me detailed notes on it. And it’s been really helpful, not just for me, but for my studio teams as well.”

Results, not personality

Mould says that accommodating neurodiversity involves switching to an output-focused mindset. “So focusing on results, not presence or personality.”

“I want people to avoid micromanagement. Nobody likes it. But I find that us neurodivergents tend to get more micromanaged because we don’t remember, and people feel the need to check on us a lot – and I don’t necessarily think that’s true when we have the right support.”

“It’s all about making sure that we have the correct things to do our job – and not pinging me every 10 minutes to make sure that something is done.”

The key is focusing on the output, not how a person behaves. “Let’s look at the work itself,” says Mould. “Let’s not look at how they show up at meetings. Let’s not look at how much they talked in Slack or Teams or whatever. What are they actually producing? And are you giving them the space to do that appropriately?”

“Lead with trust.”

The important thing for employers to note is that none of this costs anything. “My AI assistant doesn’t cost us anything, my Goblin Tools […] doesn’t cost anything, and kindness never costs us,” says Mould.

“It’s just about listening and asking people what they need. And there are so many amazing tools out there that are free.”

All it requires is an investment of time to spell out goals clearly and check employees have the right support. “But you would have to do that as a good manager anyways, even if your team was neurotypical, right? You’re going to have to think of task lists, you’re going to have to prioritise things.”

Still, in order for employees to benefit from this kind of support, they have to feel safe enough to access it.

It’s just about listening and asking people what they need”

Katherine Mould, Keywords Studios

“Safety is what’s experienced, right?” says Mould. “You can provide all the supports you want, but if people aren’t using them, they don’t know how to access them, they do not feel safe enough to do so – that’s not safe.”

“People do not use accommodations when they fear judgement.”

“There have been numerous times in my career where I have been afraid to ask for what I might actually need, for fear of what might come after.”

Above all, she thinks that the number one thing people managers need to do is provide grace.

“Grace is just allowing people to be who they are, and not punishing people for those differences,” she says.

“It’s general basic human decency in a lot of ways. Allowing people to make mistakes and learn from them, and giving grace for growth.”