Given the tumultuous changes in the games industry over the past few years, it’s worth taking a moment to look at where we are – and more importantly, where we’re headed.

In the first instalment of this two-part feature, former Sony Worldwide Studios chairman Shawn Layden, Circana senior director Mat Piscatella, and Ampere Analysis head of games research Piers Harding-Rolls offer some insights into the current status of the industry – beginning with worrying signs that US consumers are tightening their purse strings when it comes to video game purchases.

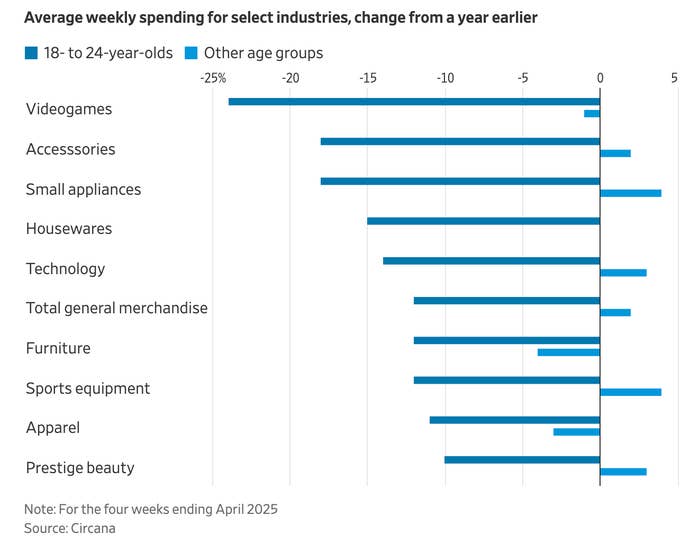

“Essentially, we have about a quarter of video game players who are saying they’re planning on spending less, driven by a number of factors,” says Piscatella, referencing a recent Circana report.

He notes that the trend is primarily down to increasing costs for things like food and housing that are causing people to look for savings, as well as the question marks surrounding US tariffs.

Layden agrees: “In America right now, because of fears of recession, because of inflationary impacts, whether they’re tariffs or just current industrial policy, everyone’s feeling like, ‘I shouldn’t spend as much as I used to spend,’ just full stop right across the board. So, of course, gaming is going to be affected by that.”

“Some of this turmoil in the international economy,” adds Piscatella, “and in particular in the US economy, has people feeling more uncertain, and uncertainty leads to a lot of people waiting on decisions, putting off big purchases, trying to better plan their finances – and that’s what we’re seeing right now in the data.”

“In this case, we have double the amount of people saying that they’re planning on spending less than are saying they’re planning on spending more. That’s a little bit of a red flag.”

This has led Circana to predict a decline of around 4.7% for the US games market in 2025, although Piscatella notes that in the current climate these things can be challenging to forecast.

“If we ended up plus 5[%] I wouldn’t be shocked. If we ended up minus 10[%] I wouldn’t be surprised. There’s so much uncertainty.”

Not recession-proof after all?

In previous global downturns, like in 2008, games earned a reputation for being ‘recession-proof’.

This is because whereas consumers tended to cut back on other forms of entertainment in times of financial turmoil, like eating out or going to the cinema, they mostly maintained their spending on games, which were seen as offering good value for money in terms of hours of enjoyment.

But, given Circana’s recent report into consumer spending plans, that doesn’t appear to be the case any more.

“I don’t know if games are recession-proof,” says Piscatella. “I think play is recession-proof, but the business models, I don’t know if they’ll be recession-proof – especially this time around. We’re going to have to find out.”

“The market now is completely different to when the last major recession happened”

Piers Harding-Rolls, Ampere Analysis

In short, given the wide availability of low-cost subscription services and free-to-play games, we may be in a situation where consumers don’t feel they have to spend money on games when times are hard.

“The market now is completely different to when the last major recession happened,” says Harding-Rolls. “There’s so much free content out there.”

“People don’t necessarily have to spend in-game or buy premium games. [Free-to-play games are] a very effective way of spending your time without spending a lot of money.”

“The whole idea of recession-proof is a bit of a misnomer, I think, because previously it was […] predominantly premium games. Things have changed a lot since then.”

Additionally, looking at the wider picture, there are clear indications that the video game market is now maturing after years of rapid growth.

There were signs of this back in 2019, when shares in game companies were being sold off en masse, and a Bloomberg report predicted imminent decline. But the COVID-19 pandemic saw those forecasts upended, as millions of people stuck at home in lockdown turned to video games to stave off boredom.

However, most of that new influx of players didn’t stick around once lockdowns had lifted.

“The actual audience is about 10% smaller than it was at that peak,” says Harding-Rolls, although he notes that many of those fairweather gamers “weren’t heavy spenders.”

Piscatella says that 2021 remains the high point in terms of the US game market.

“If you look at the comparison in spending between now and 2021, it’s been absolutely, amazingly stable. We went from a growth market to a mature market overnight.”

The difference now is where people are spending their money. “We have much more prevalence of the mobile space, of the free-to-play space, and a de-emphasization of the console space,” says Piscatella.

“Especially when you look at younger and less affluent consumers, they are choosing to go towards easily accessible games on devices they already own.”

The double-edged sword of free to play

There’s an argument that free-to-play games have de-valued video games overall, making them seem like something consumers don’t necessarily have to spend money on – especially in times of financial hardship. But Harding-Rolls points out that they’ve also been a key driver of success.

“If everything had stayed pay-to-play at a premium rate, you just wouldn’t have the size of audience and the scale of the market,” he says. “In-game monetization is worth 77% of the total market.”

“If we didn’t have any free content, what would the market look like? It would look like probably a quarter of the size it is now, realistically. I mean, it might have grown a bit, but nothing like almost $200 billion in spending.”

The trouble, perhaps, is that much of that spending is focused on a relatively small number of titles.

Piscatella points out that behemoths like Fortnite, Roblox or Call of Duty are “amazing” at funnelling in players and keeping there with social hooks. “And because [the players have] invested so much time into the games, these games now become the default. This is the video game for that audience. And so they’re locked in, right?”

At same time, he notes, there’s been exponential growth in the number of new releases. “And if you look all-in at game spending – it being flat the last several years as more and more games get released – then that math tells you the average game is making less than it was a few years ago. And on top of that, the concentration of those revenues is being allocated more towards the biggest of the big, the Fortnite, Minecraft, Robloxes, Grand Theft Autos of the world.”

“So you do all that math, and what you get is: ‘Oh boy, the crunch is very real'”

Mat Piscatella, Circana

“So you do all that math, […] and what you get is: ‘Oh boy, the crunch is very real’.”

Yet at the same time that consumers are increasingly gravitating towards titles that are free at the point of entry, there’s also been a somewhat contradictory push to raise premium game prices to $80, notably with Mario Kart World.

“That upfront price is such a barrier to get people even to try a game,” says Piscatella. “Because why am I going to spend $80 for this game when Fortnite is here, and I can just log in, and everyone’s there, and all my stuff’s there?”

“That’s why I refer to those games as the black hole games, because they suck all the time and money out of the market.”

The dilemma of $80 games

“It’s a strange cognitive dissonance,” says Layden of the way a generation has been shown they don’t need to spend money on games at the same time as publishers are saying games should be more expensive.

He points out that the retail price of premium games has remained stubbornly consistent over the past 20 or so years, despite the twin factors of inflation and exponentially rising development costs.

“I think it’s because everyone’s afraid,” he says. “No one wants to be the first one to raise the price, because you’re afraid to lose traffic. So what you do is you just end up eating into your operating income, your profit margin.”

“There were more sports cars in the parking lot in the PS1 era than there were in the PS4 era, because if you’re selling 20 million units at $60 for something that only cost you $10 million to make, that’s different than selling 20 million units at $60 for something that cost you $160 million to make.”

“There were more sports cars in the parking lot in the PS1 era than there were in the PS4 era”

Shawn Layden

In hindsight, Layden says, the price of games should have been bumped up gradually with every generation. Instead, the industry has thrown everything at growth, thinking that “as long as we grow, even though we’re not making money, somehow we can’t die.”

But we’re now at a tipping point, he thinks. “The cost of construction is just way too high. If you’re going to spend over $200 million to build a game, your margins are super tight, unless you can expect to sell 25 million units. Unless you’re Rockstar, [you] should not expect to sell 25 million units.”

Industry leaders have been trying to compensate for the exorbitant rise in game development costs in other ways. “They said, ‘Okay, what if we maintain the price and then we nickel and dime you with the DLC, microtransactions, battle pass, season pass, whatever you want to call it, and try to make up the excess there?'”

At the same time, there’s been an emphasis on deluxe editions of games that can easily cost $100 or more, pumped up with extra skins and weapons that entail “almost a zero cost” for the publisher, says Layden. “So they’ve already been kind of moving the medium price point up anyway.”

But the shift towards making $80 the standard price for premium games has already met with fierce feedback from players.

Notably, Microsoft walked back its decision to charge $80 for The Outer Worlds 2, which would have been the first Xbox game to debut at the new price point. Clearly, there’s the potential that the top end of the market could be diminished by setting higher prices, with fewer players willing to stump up the cash.

“I think what shrinks the top end of the market is not the price point,” counters Harding-Rolls. “It’s more the actual costs of developing content.”

The sheer expense of AAA development – maintaining teams numbering in their hundreds, or even over a thousand – means not only that just a handful of companies can compete at this level, but also that innovation will necessarily drain away from the higher end of games as publishers become more risk averse.

“So the consumer is not necessarily getting exposed to the most dynamic and interesting development in the game space,” he says.

Layden agrees. “I think it’s going to be harder for innovation to occur at that price point, because when you get to that kind of cost – $200 million, $250 million to make a game – in most studios, risk tolerance goes to zero.”

As such, anything targeting the $80 price bracket is likely to either be a sequel or something that’s similar to another game that sold well – a ‘comparable’.

“I think it’s going to be harder for innovation to occur at that price point”

Shawn Layden

“Sadly, anyone who’s trying to break new IP at that price point, at that cost point… I mean, I’m not saying it can’t be done, but there are a lot of long, hard nights during that development cycle if you’re trying to push out a new IP at $200 million into that price point. That’s called working without a net.”

Whatever happens, it feels like the higher end of the market will inevitably get higher still, or at least attempt to.

Piscatella compares it with how the game pad market has evolved from a space that sold a wide range of affordable pads to one that’s almost entirely centred around deluxe and extremely expensive devices.

“[They] started realizing that the console consumer is getting older and more affluent,” he says. “They started putting out higher priced game pads, more premium game pads. And now these are the devices that are leading the market.”

It’s similar thinking when it comes to $80 games, Piscatella explains. “We have an audience that is not growing on the console side. We have an average console buyer that is older and more affluent than […] five years ago. They’ll still pay it, and then the rest of the audience will eventually get there through either discounting or promotion over time.”

“So it’s going to work for the big games. For the games that are successful, it’s going to work well.”

He notes that expensive deluxe editions of games already perform admirably at launch in comparison with standard editions.

“The versions of those games that will sell better are the higher-priced versions, because you have a less price-sensitive consumer there on day one. And the games that don’t, you drop the price quickly, you price promote quickly, but at least you captured some of those price-insensitive consumers at launch.”

A wild west of pricing

But $80 games are only part of the story. Across the high, mid and low ranges, pricing has become far more dynamic.

“I think what we’re seeing is more diversity of launch pricing and promotional strategy post launch than we’ve ever seen before,” says Piscatella. “We’re seeing games being released at all ends of the spectrum when it comes to pricing, and folks are going to charge for their game what they think they can most get away with.”

“Some games you look at and go, ‘What are you thinking?’ Because internally, they’ve convinced themselves that we have the secret sauce and this is going to be the biggest game in the world, or because their financial plan demands that they have a big revenue day one, even though everyone on the team might know that’s a little bit of a pipe dream.”

He reckons this pattern of diverse pricing will continue. “I think we’re going to see a lot of experimentation,” he says.

“Everyone kind of dabbles and tries to figure it out, and then it gets optimized into oblivion – like we see on the Steam summer sales now, where it used to be the wild west of discounting and pricing all over the board, and now you pretty much know what you’re going to get every summer when that sale comes around.”

Piscatella continues: “There’s a lot of vibes-based pricing analysis that goes into launch pricing these days. Of course there’s a lot of very smart people doing it, with all kinds of charts and graphs, but because of the volatility, because there’s so many different ways of going about it, a lot of the times it boils down to, ‘I don’t know, this feels like a $50 game, this feels like a $70 game’ – which isn’t the best way to do it, but that’s the way it’s still done a lot of the times.”

“No one wants to pay money to come into the studio and watch people code”

Shawn Layden

To confuse things even further, we now have subscription models that completely upend traditional ideas of pricing – and contribute to the idea among the general public that games should cost hardly anything at all.

“I’m not a big supporter of the ‘Netflix of gaming’ idea,” says Layden. “I think it is a danger.”

“I mean, look what happened to music. In the popular mind, music costs nothing. Music should be free. Spotify, what is that? It’s 15 bucks a month or something, but virtually no one buys music anymore.”

The one silver lining, he says, is that music artists have “an adjacent market” in the form of touring, allowing them to rely more heavily on ticket sales and merchandise as a key revenue stream.

“The problem with gaming is all we have is launch. That’s it. No one wants to pay money to come into the studio and watch people code.”

All of this is why he thinks that putting games on subscription services on day one is “bad for the business.”

“No lesser light than Strauss Zelnik himself has said GTA is never going on a subscription service day one,” Layden points out. He acknowledges that the situation might be different for indie developers who crave discovery above all else, but for AAA games, he questions the idea of launching day one on subscription services like Xbox Game Pass. Now that idea is out there, however, it’s difficult to go back. “You can’t unring the bell, right?”

But beyond the financial wisdom of making new games available for ‘free’ at launch, Layden worries about the change in ethos behind it.

“There’s a lot of debates going on. Is Game Pass profitable? Is Game Pass not profitable? What does that mean? That’s really not the right question to ask anyway.”

“You can do all kinds of financial jiggery-pokery for any sort of corporate service to make it look profitable if you wanted to. You take enough costs out and say that’s off the balance sheet and, oh look, it’s profitable now. The real issue for me on things like Game Pass is, is it healthy for the developer?”

Under the subscription model, the developer essentially becomes a “wage slave,” he argues.

“They’re not creating value, putting it in the marketplace, hoping it explodes, and profit sharing, and overages, and all that nice stuff. It’s just, ‘You pay me X dollars an hour, I built you a game, here, go put it on your servers’.”

“I don’t think it’s really inspiring for game developers.”

Part two to follow.

In the initial version of this article, several quotes at the end of the section ‘The dilemma of $80 games’ were incorrectly attributed to Shawn Layden instead of Mat Piscatella. This has now been amended.