How many people came up with the idea to launch a Squid Game video game after the Korean TV show broke Netflix records in 2021? The answer, with one glance at the cursed depths of mobile game stores, was plenty.

In his ‘Demystifying Creativity’ talk at this year’s Nordic Game conference, Ubisoft’s Fawzi Mesmar – who’s been creative director of the long-gestating Beyond Good & Evil 2 at Ubisoft since October 2024 – uses a Squid Game video game as an example of an ‘inevitable’ idea. He mentions a friend who watched the show, came up with the idea to adapt it into a game, then realised he’d been beaten to the punch by a ton of unconvincing-looking Squid Game ripoffs.

By ‘inevitable’ idea, Mesmar means that anyone could’ve come up with it. Millions of people watched Squid Game, and its video game-like premise of a hundred people risking their lives in a series of deadly games to win a cash prize offers obvious potential.

Originality is not exactly the same as creativity, Mesmar cautions in his talk. An idea isn’t valuable just because it’s original – waterproof teabags is one deliberately funny example Mesmar gives of an original idea that has no value – and context determines the value of an idea.

Self-imposed restraints

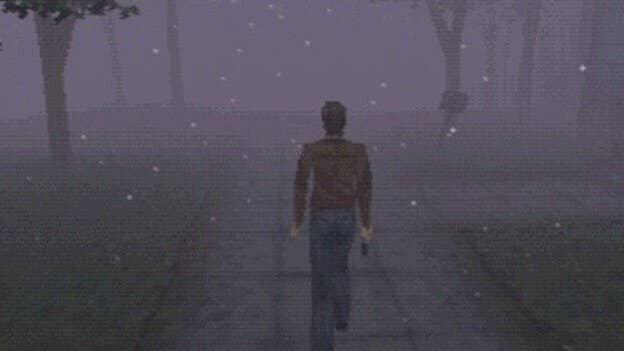

To illustrate this, Mesmar offers up the well-known example of the original Silent Hill on PlayStation with its use of fog and the radio. A solution to the limitations of how many objects could be displayed at once to the player, both elements would then become trademarks of the series.

Creativity comes from restraint – this is an evergreen idea, and those restraints can be technical, financial, or something logistical like the size of a development team.

These restraints are often self-imposed by design, too, to stimulate the quality of the resulting ideas. A haiku, Mesmar says, is an example of a self-imposed, rigid structure that has yielded hundreds of years of great poetry. Games have plenty of similar examples, Mesmar points out.

2018’s God of War, which presents its story of Kratos and son Atreus all in one ‘shot’ with no visible loading screens, is an example of a self-imposed restraint that elevates the experience. It also prompted problem solving by the developers that enhanced the game’s character: long conversations between father and son in boats or on elevators, for example, are partly there to hide loading screens, but are among the game’s most memorable storytelling techniques.

Creative thinking

Mesmar’s formula for measuring creativity essentially asks the question, ‘how did you come up with this idea?’ The answer to this question involves dissecting which components of the idea can be attributed to your life journey, cultural background, or particular perspective, and which might be shared with others who consume the same pop culture influences or perceive the world in the same way.

Mesmar calls this process Creative Sobriety, which he expounds upon in his book, Demystifying Creativity. The origins of the book came from his own experiences as a developer and teacher.

“I’ve been teaching game design and universities and schools for quite some time,” Mesmar tells GamesIndustry.biz. “I’ve also been leading game design teams in various places around the world [for] quite some time as well. And I started to see patterns in how people come up with ideas. I’ve witnessed some teams or students get so excited about an idea that they’d want to quit their job and pursue that idea the next day.”

Mesmar says, though, that some of these ideas would’ve already come up two or three times in the same week, suggesting they weren’t as unique as first assumed.

“I started to see patterns in how people come up with ideas”

Fawzi Mesmar, Ubisoft

“So I started thinking to myself, why is that keeps on happening? It can’t be a coincidence. There must be a pattern in how our brains function, or how those classes are structured, or something. There must be a reason for why and how we come up with ideas to begin with. And then I became – [as] some of my friends put it – slightly obsessed with creativity, [with] the notion of, ‘how do we even come up with ideas?'”

That’s when Mesmar started looking into the process in more detail.

“I thought to myself, if we’re able to understand that, then that will help us arrive better at originality. So I started to [make] a lot more observations on the topic, read a lot more on the topic, and [did] some thought experiments with my students or my teams. And I wanted to record all of these observations and studies and research into this book that I just released.”

I had that idea

The goal of Creative Sobriety, then, is to intellectually improve your odds to get to statistically less likely ideas. Passing this kind of thinking down to students, in formative stages of becoming game developers, was a “big part” of why Mesmar wrote the book.

“I don’t know a single game developer, myself included, that at some point [hasn’t seen] a game come out, and said, ‘I had that idea’. Then, they get upset – ‘I should have done this idea, [but] better’, and all of that.”

“But now that I understand how that works, and I can actually go, ‘of course, you would have had that idea, because it’s an idea that many people would have had’. This is why for the students, I’ve managed to teach them to inject themselves a lot more into the ideas that they [generate]. So, not just to create based on what we see, but also to create also based on how we see the world; our own interpretation of things, our own thoughts and feelings about things as well.”

It’s not massively scientific – but that’s actually what’s stimulating about the principles of Creative Sobriety. Anyone working in any creative field will parse Mesmar’s notions of what makes something original, and what doesn’t. And everyone has a distinctive set of life experiences to draw upon, whether they realise it or not.

Mesmar says part of understanding the originality of your ideas is breaking down why you find them interesting to begin with.

“Creative sobriety is for you to become more aware of who you are as a person,” Mesmar says. “It’s a practice of self-awareness. What are my views and thoughts [about] the world? Why is this thing interesting to me? What part of my life journey was triggered or impacted by a particular input, and what caused me to be able to react to that?”

Creators aren’t powerless to expand the pool of influences they draw upon, too, of course.

“What I’m advocating for is a combination of life experiences and being able to think more about things from your own angle; [being able to] feel or articulate your feelings about certain things, and creating, let’s say, a web of association. That then gives you a complex web that is completely unique to yourself, that will generate ideas that are more likely to be completely unique to yourself.”

Mix and match

Not every successful game idea is an original idea – and sometimes a combination of several existing ideas is original. Last year’s game-of-the-year contender Balatro, for example, is a combination of familiar game concepts, but the execution is totally distinctive.

We ask Mesmar if he thinks an inevitable idea is ever the right one. “So ‘right’ is a very interesting question, because it’s right to whom? The ‘inevitable’ idea is a direct level of association. If I say colour, [and] you say pink – that’s a correct answer. But the likelihood of someone else thinking of this is quite high.”

Again, context is key – the colour pink might be the solution to the situation at hand.

“It’s not necessarily me saying that inevitable ideas are bad ideas. In fact, those ideas are too good, to the point that it’s inevitable that someone else would think of them. Within the context of answering the problem, those ideas are the right ones.”

The difference comes when your goal is strictly about originality, according to Mesmar.

“Within the context of arriving at originality, those ideas are not enough, is what I’m advocating for. The context of arriving at originality means that we need to come up with an answer that is less likely for someone else to think of. Therefore, within that context, that is not the right answer, but if it was to just answer the question, they’re absolutely the right answer. And that distinction is at the heart of Creative Sobriety that I’m talking about.”

“We need to come up with an answer that is less likely for someone else to think of”

Fawzi Mesmar, Ubisoft

All this talk of ‘creative sobriety’ might sound like something cultish, but Mesmar’s understanding of how creators think is thought-provoking, and his ideas are explained so cleanly that they stick in the memory. His talk comes highly recommended, if originality is the goal on any project. It highlights the limitations of a person or team’s capacity to come up with ideas, but also spotlights hidden strengths, too.

“For me, when I do a talk, or when I do a lecture, or even when I work with someone, it’s always a lot more fruitful if I take you with me on that journey,” Mesmar says. “If I just come in and give you the summary, I can summarise the talk in five minutes. But the takeaways on their own, without taking [you] on the journey, [would] be met with reactions like, ‘I agree’ or ‘disagree’ or ‘what a wild claim, where did that come from?'”

“There are all kinds of ways to challenge it, which is valuable. But if I take you away on the journey with the reasoning that I’ve had, you’re more likely to believe in what I have to say.”

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. GamesIndustry.biz was a media partner for Nordic Game 2025, with travel and accommodation paid for by the organisers.